Do you know the last time I saw a doctor? 10 months ago. A 15-minute checkup, six weeks after birth.

If you’ve been through it, you know the drill.

Six weeks after literally producing a new human, your doctor gives you a quick once over, ok’s you to start having sex again (as if that’s what you’re thinking about!), and you’re waved out the door.

But a new Science Advances study revealed something women have long known: it takes a lot more than six weeks postpartum to “return to normal”.

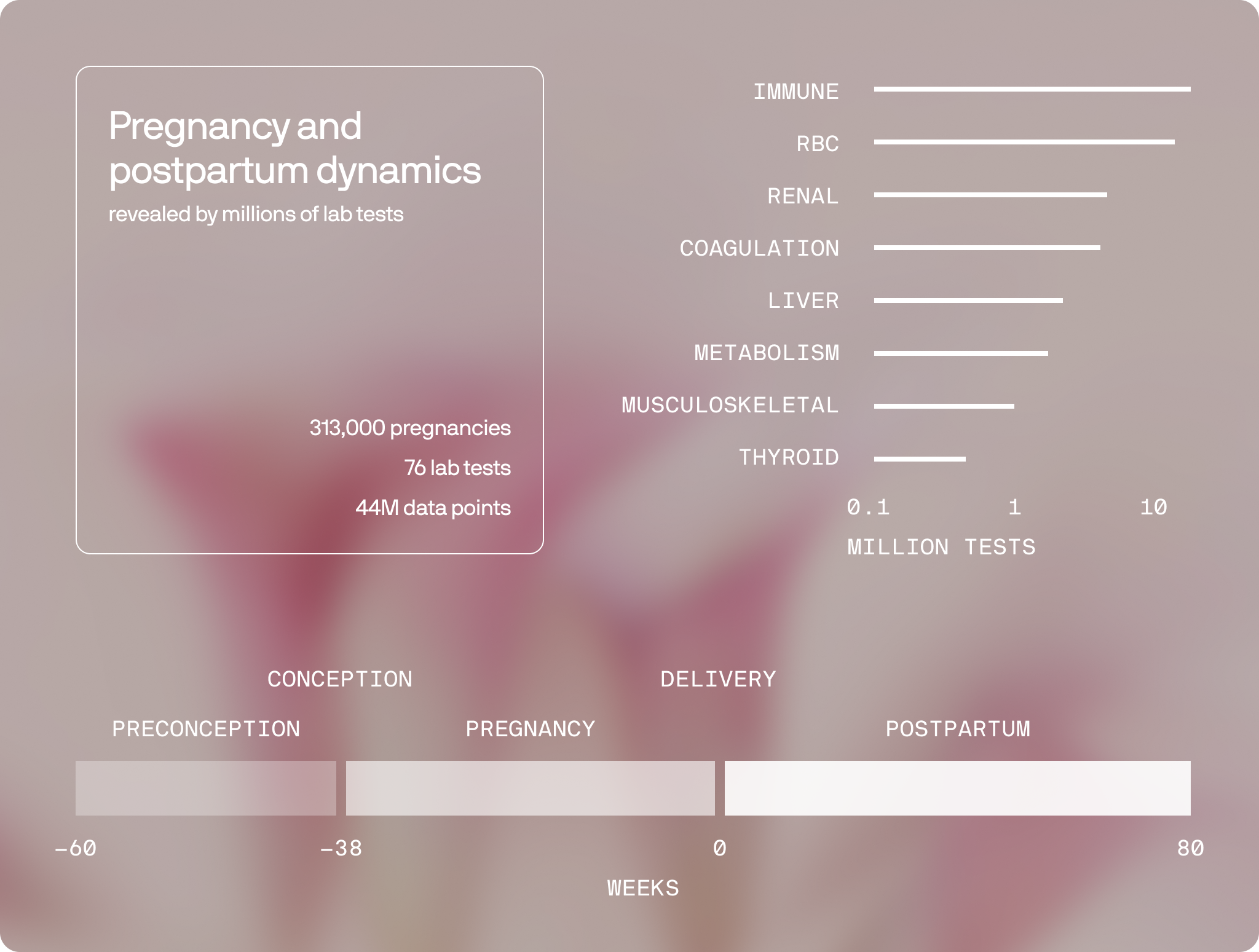

The study analyzed 44 million test results from over 300,000 pregnancies, tracking 76 biomarkers from 20 weeks before conception to 80 weeks after birth.1 The big takeaway? Your biomarkers can take up to a year to return to baseline.

So what does this mean for your health and how you recover postpartum?

Before we dive into the findings…let’s start here: What are biomarkers, and why should you care about them?

How biomarkers decode pregnancy and postpartum health.

Biomarkers are essential for tracking health, especially in the context of pregnancy and postpartum recovery (you feel kind of terrible all the time).

Your body is working double-time to grow a baby, create milk, and recover. And during this time, normal changes can also overlap with medical issues.

But sometimes, that fatigue isn’t just “part of pregnancy.”

One of the most common hidden causes of fatigue is anemia, often from low iron or vitamin B12 — nutrients your baby is drawing from your stores. The issue is you often can’t tell the difference by how you feel. The only way to know is with a blood test.

That’s the power of biomarkers: they turn vague symptoms into clear indicators.

Okay, now onto those findings. So, what exactly did this study find? And what does it mean for the pregnancy and postpartum experience?

Biomarker recovery postpartum is long and gradual.

Postpartum recovery isn’t some 6-week milestone. It’s a long, (invisible) biological marathon.

The study revealed:

- Nearly half of lab markers calmed within a month after birth

- About 1 in 10 took a few extra weeks

- The rest took months, even up to a year, to find their rhythm again.

This data demands we re-think how we approach postpartum care — it’s a 12-month process, not a 6-week box tick. And knowing which markers change (and how long they take to heal) could transform how we manage our health before, during, and after pregnancy.

To dig even deeper, the study showed:

- 54 out of 76 biomarkers showed clear pregnancy/postpartum shifts

- About half settled within 4 weeks post birth

- 12% of biomarkers settled between 4-10 weeks after giving birth

- 41% took more than 10 weeks to stop fluctuating, this included:

- Liver enzymes AST and ALT, which pinpoint if your liver is working too hard, take about six months to recover.

- Cholesterol and other metabolic lipids, indicators of heart disease risk, take months to baseline.

- Alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme linked to bone and liver function, only after about a year.

- Several tests did not return to preconception baseline by the end of follow‑up at 80 weeks:

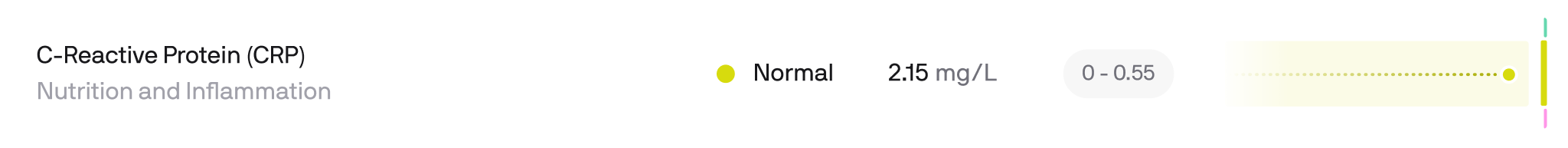

- CRP (C-reactive protein): stayed high, a sign of ongoing inflammation.

- TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone): trended lower, which can affect energy and mood.

- Iron indices can lag, reinforcing the value of follow-up testing.

Every system gets a rewrite after birth. The immune system is one of the first to show just how deep those changes run.

Your immune system rebalances after birth.

Pregnancy reshapes immunity in phases. Early pregnancy and labor are pro‑inflammatory to support implantation and delivery, while mid‑pregnancy is more anti‑inflammatory to protect fetal growth2.

In the study CRP (C-reactive protein), which tracks persistent, low grade inflammation, never returned to normal by the end of 80 weeks.

But mums who started supplements early (especially folate and B12) had calmer inflammation and steadier recovery. Big win for actually taking your vitamins.

Strangely, those with existing autoimmune conditions often experience some easing during, pregnancy itself3, but then return in the first 3 to 6 months postpartum4. Like Rheumatoid Arthritis, which often flares up again within ~3 months postpartum5.

Check: If you notice unusual pain, swelling, or fatigue, it’s absolutely worth checking your inflammatory markers.

🦸 If you want to learn more on CRP, read Inflammation Biomarker Testing.

Long-term surprises.

Beyond recovery itself, pregnancy reshapes your biology in ways that echo through your longevity and future health.

- Biological age reset: Pregnancy is associated with epigenetic age acceleration - basically your body temporarily looks ‘older’ on DNA methylation clocks. After birth, there’s a postpartum reversal back toward baseline, which seems to be stronger among breastfeeding mothers4.

- Your baby’s cells are in you: Fetal cells can persist for decades in maternal blood and tissues and may participate in tissue repair, although they can also contribute to immune phenomena6.

- Future health: Pregnancy, and especially longer breastfeeding, lowers long‑term breast cancer risk and reduce ovarian cancer risk7. Complications such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes signal higher later‑life risks of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Beyond blood-tests.

And it’s not just your blood. Your microbiome (especially in the vagina) undergoes a massive transformation.

During pregnancy, rising estrogen and progesterone reshape the ecosystem, encouraging protective Lactobacillus species that lower pH and help guard against infections. After birth, when hormone levels plummet, that microbial balance shifts again.

This also affects the health of your baby. Vaginal delivery births give babies a more diverse microbiome early on*,* and babies acquire oral microbiota from caregivers via kissing, sharing spoons, pre-chewing food and even their delivery method8.

Breastfeeding further boosts oral bacteria, adding good bacteria (like Lactobacilli) through skin contact and breastmilk9.

Bone density takes a short-term hit, but typically rebounds within a year postpartum.

Calcium and vitamin D demands also soar during pregnancy and breastfeeding, with mom’s skeleton stepping in as a temporary “mineral bank” for the babies demands.

One study showed that moms experience 5–10 % bone density loss from the spine over the first 6 months postpartum10.

What this means for you (or someone you love).

- Before pregnancy: Know your baseline (blood sugar, lipids, thyroid, vitamin D).

- During pregnancy: Monitor glucose, iron, thyroid, and inflammation if recommended.

- After pregnancy: Don’t stop at 6 weeks. Recheck key labs at 3–6 months, and again at 1 year.

Some moms are back at CrossFit by week eight. Some never feel “baby brain.” Both are valid. But the data shows us it takes years to be ‘back to normal.’ And sometimes, our biochemistry changes permanently.

Your path is personal. Check your biomarkers. Listen to your body. And move at the pace that fits your pregnancy and postpartum story.

Get your biomarkers tested today.

References

[1] Alon Bar et al. ,Pregnancy and postpartum dynamics revealed by millions of lab tests.*Sci. Adv.*11,eadr7922(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adr7922

[2] Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Mar;1221(1):80-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05938.x. PMID: 21401634; PMCID: PMC3078586. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3078586/

[3] Christian LM, Porter K. Longitudinal changes in serum proinflammatory markers across pregnancy and postpartum: effects of maternal body mass index. Cytokine. 2014 Dec;70(2):134-40. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.018. Epub 2014 Jul 28. PMID: 25082648; PMCID: PMC4254150. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25082648/

[4] Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Moreau T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jul 30;339(5):285-91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390501. PMID: 9682040. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199807303390501

[5] Mouyis M. Postnatal Care of Woman with Rheumatic Diseases. Adv Ther. 2020 Sep;37(9):3723-3731. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01448-1. Epub 2020 Jul 29. PMID: 32729009; PMCID: PMC7444396. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7444396/

[6] Pham, Hung et al, The effects of pregnancy, its progression, and its cessation on human (maternal) biological aging, Cell Metabolism, Volume 36, Issue 5, 877 - 878 https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(24)00079-2

[7] Bianchi DW, Zickwolf GK, Weil GJ, Sylvester S, DeMaria MA. Male fetal progenitor cells persist in maternal blood for as long as 27 years postpartum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Jan 23;93(2):705-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.705. PMID: 8570620; PMCID: PMC40117. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8570620/

[8] National Cancer Institute, Reproductive History and Cancer Risk: Fact Sheet, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/reproductive-history-fact-sheet

[9] Lif Holgerson P, Harnevik L, Hernell O, Tanner ACR, Johansson I. Mode of Birth Delivery Affects Oral Microbiota in Infants. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90(10):1183-1188. doi:10.1177/0022034511418973 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022034511418973?

[10] Holgerson PL, Vestman NR, Claesson R, Ohman C, Domellöf M, Tanner AC, Hernell O, Johansson I. Oral microbial profile discriminates breast-fed from formula-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Feb;56(2):127-36. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2bc6. PMID: 22955450; PMCID: PMC3548038. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2bc6

[11] Christopher S Kovacs, Pregnancy and Lactation Associated Bone Fragility, Journal of the Endocrine Society, Volume 9, Issue 9, September 2025, bvaf126, https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaf126

.svg)

.png)

.png)

.avif)