Grilling feels like summer on a plate. The smoke in the air. The sizzle of searing meat. That lazy backyard vibe.

Which is great for your health, right? Grilling uses less fat than frying and often gets more veggies onto your plate.

But high, dry heat has a dark side. Cooking meat (and even plant proteins) over intense heat creates compounds your body doesn’t handle well.

These chemicals are linked to inflammation, insulin resistance, and higher risks of certain cancers.

The good news? You don’t need to give up the grill.

By understanding the four main culprits (HCAs, PAHs, AGEs, and NOCs) and making a few simple (and delicious!) tweaks, you can keep the flavor and cut the risk.

The 4 chemicals of the Grill-pocolypse

Ever wonder why grilled meat smells so good that it practically hijacks your brain?

Grilling comes with a side of unfamiliar biochemicals, some of which your body isn’t thrilled about.

Before you accuse me of being the world’s biggest kill-joy, the occasional charred lamb chop won’t kill you.

But grill smarter and know the four byproducts (HCAs, PAHs, AGEs, NOCs) that bring flavor, but also bring risk.

HCAs: high-heat’s hidden hazard

Muscle meats naturally contain amino acids and creatine - yes, the same creatine that sometimes shows up on your blood tests or in sports supplements.

When meat is exposed to high, dry heat, like grilling, broiling, or pan-frying, these interact to form compounds called Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines (HCAs).

The hotter and longer the cook, the more HCAs you get.

HCAs can bind to DNA, causing mutations2 and changing how the liver processes fats3 .

In a 2022 meta-analysis of nearly 2 million people, those eating the most meat-derived HCAs had about a 20% higher risk of cancer compared with those eating the least4.

PAHs: smoke-borne troublemakers

When fat drips onto hot coals or flames, it burns and releases smoke rich in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

These are the same pollutants found in urban air pollution and cigarette smoke, and during cooking can stick to the surface of food or get inhaled.

Similar chemistry happens in other high-smoke cooking, like tandoor baking, wood-fired ovens, or smoking meats. But unlike HCAs (which form mainly in muscle meats), PAHs can contaminate both meat and plant foods.

Once PAHs enter the body, your liver tries to break them down, but ironically, this can turn PAHs into even more reactive forms that bind to DNA, potentially causing mutations.5 .

In a large U.S. health survey, people with the highest urinary PAH levels were about three times more likely to have diabetes than those with the lowest6 - a red flag even if it doesn’t prove cause.

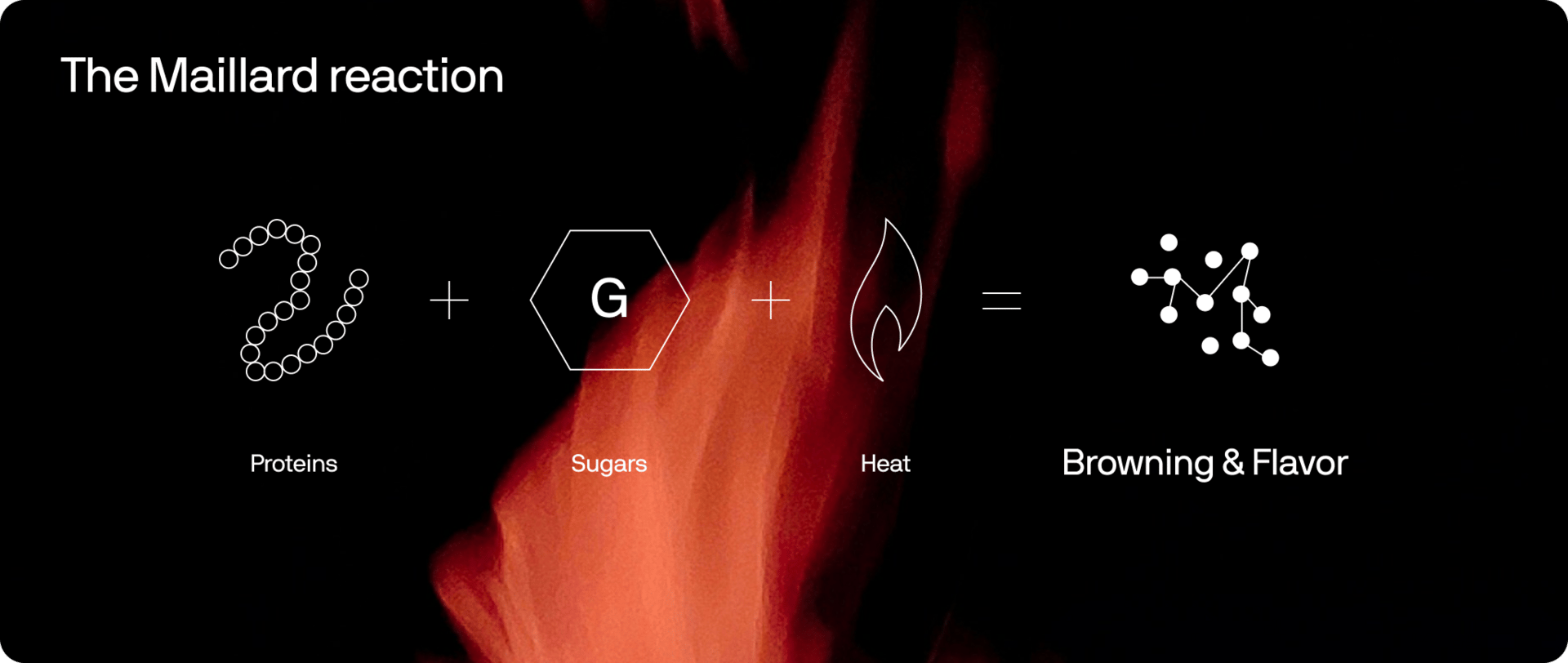

AGEs: browning that ages you

Sunbathing isn’t the only browning that can age you.

Inside your body, sugars naturally bind to proteins and fats - a process called glycation - forming Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs).

This happens slowly over time, but high, dry cooking heat can supercharge it.

When you grill, roast, or fry, sugars in food react with proteins or fats in a process called the Maillard reaction. It’s what makes steak crusty, toast golden, or cookies deeply browned.

Raw meats and dairy contain some AGEs, but dry-heat cooking can create 10–100× more7.

The biggest offenders: seared red meats, fried or roasted poultry, bacon, and hard cheeses.

High-AGE diets are linked to glucose intolerance, insulin resistance8, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation.

In one clinical trial, cutting AGEs for just four months improved insulin sensitivity and markers of vascular health9.

🫘 Note on plant-based proteins: A little Maillard browning can make soy, pea, chickpea, oat, or rice proteins taste richer and less “beany.” But push the char too far and you’ll still rack up harmful AGEs - and if it’s over open flame, some PAHs too. The trick is control, not avoidance.

N-nitroso compounds (NOCs): a processed meat problem

N-nitroso compounds (NOCs), including nitrosamines like NDMA and NDEA, form when nitrites (preservatives that keep hot dogs fresh, bacon pink, and cure meats) react with amines during high-heat cooking or in the acidic environment of your stomach. 10 11 .

These potent carcinogens damage DNA, drive inflammation, and are linked to cancers of the pancreas, liver, and gut10 . They also drive inflammation, oxidative stress, and disrupt your liver’s metabolism11 .

Processed meats - bacon, ham, hot dogs, sausages - are a major source. Eating just 50 g a day (about two bacon slices or one hot dog) bumps colorectal cancer risk by ~18%14.

One extreme example: Chinese-style salted fish is classified as Group 1 carcinogen due to it’s association with nasopharyngeal (throat) cancer15 .

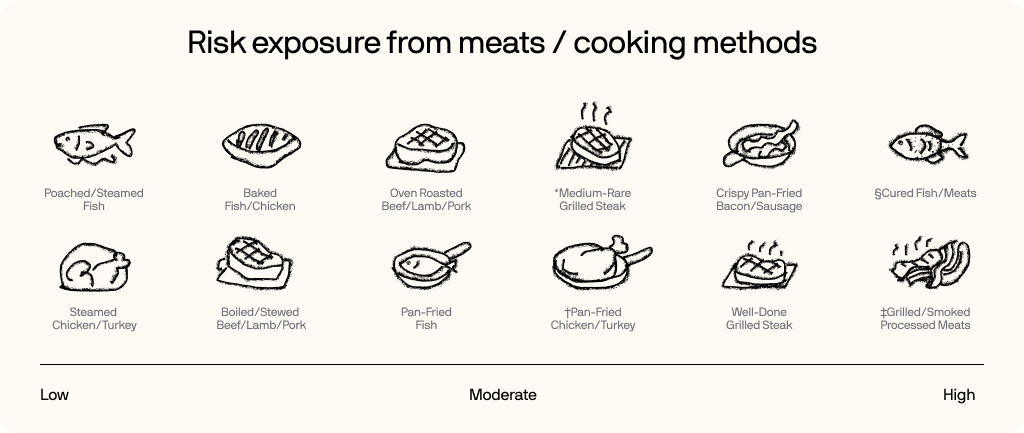

Which meats produce the most harmful compounds?

The type of meat, and how you cook it, affects toxin formation. Fat content, muscle type, and curing methods all matter.

But remember, any meat can form meat mutagens if cooked to a crisp. “Safer” doesn't mean risk-free, just lower risk.

Quick Takeaway:

- Safest: Low-fat cuts or meats, gentle heat, moist cooking, minimal browning.

- Moderate risk: Brief pan-frying, roasting, grilling without heavy charring.

- Eat sparingly: Charred, grilled, processed, and heavily fried meats.

- See footnotes for more details and nuance 1.

A note on sourcing: Grass-fed and pasture-raised meats tend to have a healthier fat profile and higher antioxidant content.

While they can still form HCAs, PAHs, and AGEs when overcooked, their baseline nutrient quality gives you a better starting point. Think of it as upgrading the raw ingredients before you start managing the cooking risks.

Smart ways to lower toxins when cooking meat

Beyond our body’s natural detox defences16 , some simple tips can reduce your exposure:

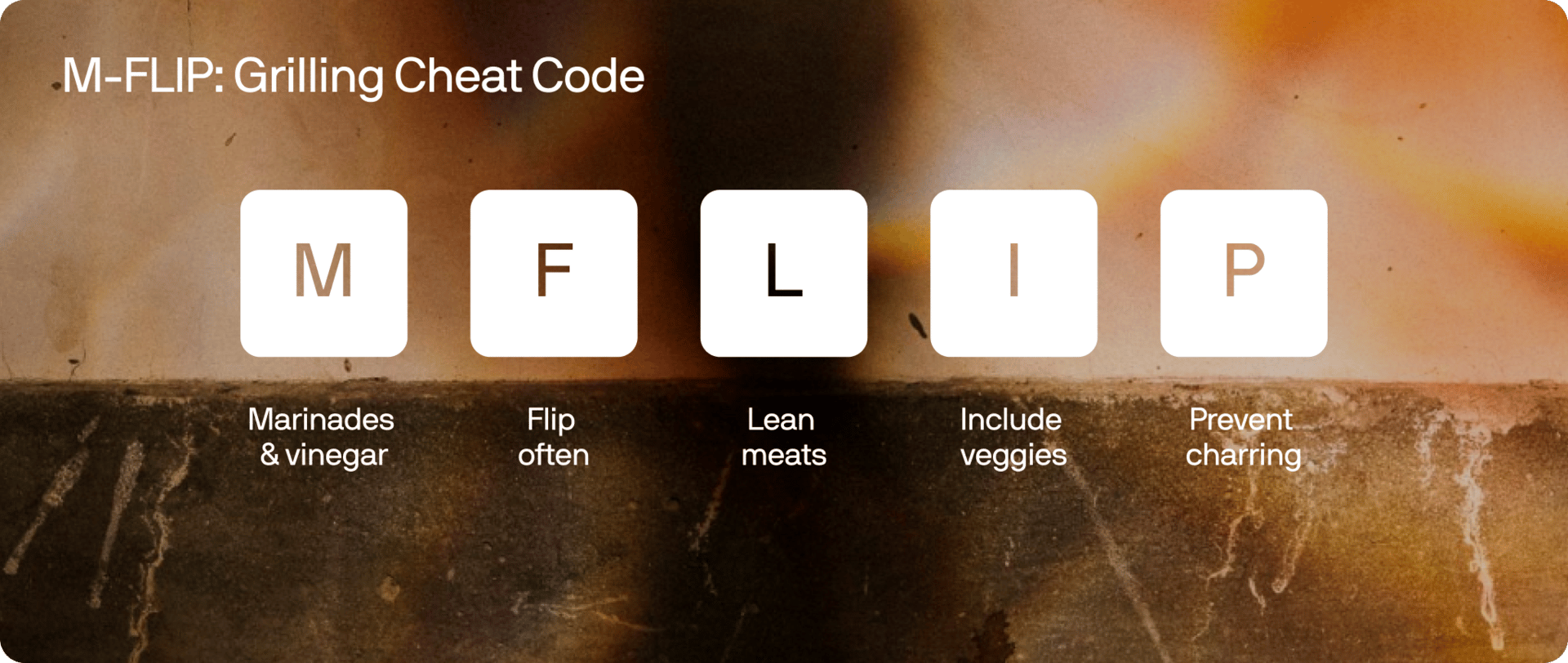

Marinate your meats with flavorful antioxidants

Using marinades with antioxidant-rich ingredients like rosemary, turmeric, garlic, lemon juice or olive oil can significantly reduce HCA formation. Beef steaks marinated for 1 hour in spice-rich blends had 88% lower total HCA levels17 and marinated chicken cut HCA content by 92–99%18 . Avoid sugar-heavy marinades as this can actually increase AGEs.

Use vinegar to slash HCAs

Marinating meat with vinegar for 30+ minutes can slash harmful HCAs that form during grilling. The acid slows the chemical reaction, making your BBQ safer and tastier19.

Flip frequently & avoid blackened edges

Turning meat often prevents surfaces from overheating and forming too many HCAs and PAHs20 . Flipping a burger every 30-60 seconds can significantly reduce HCA production21 . Removing charred bits before eating further lowers exposure.

Trim excess fat & choose leaner proteins

Reducing fat content (e.g., by removing skin or trimming) minimizes smoke production and PAH exposure. When grill drippings were eliminated (using drip trays or otherwise), the total PAHs on the meat dropped by 48–89% compared to normal grilling22 . Use indirect heat or drip trays to prevent fat-to-flame contact.

Grill more veggies

Veggies don’t make HCAs (no creatine, no problem). Some even help your body clear the HCAs you get from meat. In one study, 20 men ate half a kilo of broccoli and brussels sprouts every day for 12 days. Then they grilled meat. Their bodies flushed out ~30% more HCAs23 . Broccoli and brussels sprouts pack glucosinolates, compounds your detox system loves. Just don’t over-char them, or you’ll invite PAHs and AGEs to the party.

Here’s a quick ‘cheat code’ we like to use for safer grilling (pronounced mmm-flip — because, delicious 🤤).

You don't have to give up the grill to eat better. Just be smarter about it.

But one thing you should give up? Wire-bristle grill brushes.

They shed tiny metal bristles that can stick to your grates, hide in your food, and end up in your mouth… or worse, lodged in your throat or gut24. Use some lemon, half an onion, or a nylon brush instead.

Pick leaner cuts, throw some veggies on the side, marinate like your health depends on it (because it kind of does) and keep the flames low.

Reviewed by Julija Rabcuka, BA (Oxon), MSc, PhD (ABD), University of Oxford.

.svg)

.png)

.png)

.avif)